This leaflet aims to answer your questions about having an exenteration. It explains the benefits, risks and alternatives, as well as what you can expect when you come to hospital. If you have any further questions, please speak to a doctor or nurse caring for you.

Why should I have a pelvic exenteration?

This surgery is generally carried out on patients when the disease has come back after the initial treatment. The aim of this surgery is to cure the patient of disease. If a patient has symptoms in the area where the cancer has returned, the surgery may relieve some of these symptoms. Occasionally, this type of surgery is offered as a primary treatment.

What is a pelvic exenteration?

A pelvic exenteration is a major surgery during which some of the organs of the pelvis are removed. This surgery is normally offered to women who have already had treatments for a gynaecological cancer. The cancer has either returned or had not been cured by the initial treatment.

This surgery is very complex and takes many hours to carry out. There are different types of pelvic exenteration and which type is needed depends on where the cancer is situated. Some women will already have had their womb or their ovaries, or both, removed in their initial treatment. Other women will not have had gynaecological surgery but received chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Some may have had both types of treatment.

There are different types of pelvic exenteration. These include:

- Anterior exenteration – this is when the bladder and internal reproductive organs are removed.

- Posterior exenteration – this is when the lower part of the large bowel (rectum) and internal reproductive organs are removed.

- Total exenteration – this is when the bladder, rectum and internal reproductive organs are removed.

This means that it will usually be necessary for you to have one or two stoma bags to collect bowel and urine contents. The type of surgery you have will depend on the type of cancer and individual situation. Recovery after the surgery can be difficult, both physically and emotionally. Your surgeon or nurse can help you decide whether you want the surgery or not. It’s helpful to include a partner, family member or close friend so they can support you.

Are there any alternatives?

This surgery is only performed if there is a good chance of it curing the cancer. You will probably have had radiotherapy already. The highest doses of radiotherapy will have been used and radiotherapy cannot usually be used again in the same place, as it will cause too much damage to your bowel, bladder and other normal tissue and bone. Chemotherapy and/or hormone treatment might keep your cancer under control, but neither will cure it completely.

What needs to happen before surgery?

Before you decide whether or not to have the surgery, your doctors will have to make sure the cancer hasn’t spread outside of the pelvic area. If it has, you won’t be able to have the surgery as it won’t cure the cancer. You will also need tests to make sure you’re fit enough.

Prior to surgery you may have one or more of the following tests:

CT (computerised tomography) scan

A CT scan takes a series of x-rays, which builds up a three-dimensional picture of the inside of your body. The scan takes 10-30 minutes and is painless. It uses a small amount of radiation, which is very unlikely to harm you and won’t harm anyone you come into contact with. You’ll be asked not to eat or drink for at least four hours before the scan.

You may be given a drink or injection of a dye, which allows particular areas to be seen more clearly. This may make you feel hot all over for a few minutes. It’s important to let your doctor know if you’re allergic to iodine or have asthma, because you could have a more serious reaction to the injection. You will be able to go home as soon as the CT scan is over.

PET-CT scan

This scan combines a CT scan and a PET (positron emission tomography) scan. A PET scan uses low-dose radiation to measure the activity of cells in different parts of the body. PET-CT scans give more detailed information about the part of the body being scanned. Sometimes, they can show up areas of cancer that may be missed by other scans.

Before you have the scan, you’ll have a mildly radioactive liquid injected into a vein, usually in your arm. The radiation dose used is very small. The scan will be done about an hour later and usually takes 30-90 minutes.

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scan

This scan may be done to help plan the surgery. It’s similar to a CT scan, but uses magnetism instead of x-rays to build up a detailed picture of areas of your body. It may be done to help the surgeons plan the surgery you are going to have. Before the scan, you’ll be asked to remove any metal belongings, including jewellery. Some people are given an injection of dye into a vein in the arm.

This is called a contrast medium and can help the images from the scan to show up more clearly. During the test, you’ll be asked to lie very still on a couch inside a long tube (cylinder) for about 30 minutes. It’s painless, but can be slightly uncomfortable, and some people feel a bit claustrophobic during the scan. It’s also noisy, but you’ll be given earplugs or headphones.

If tests show that a pelvic exenteration is suitable for you and you want the surgery you will meet with your surgeon before the surgery to discuss the details. You will also meet a nurse called a stoma nurse who can help you understand how you will go to the toilet after the surgery.

Physical preparation

Your doctors also need to make sure you’re physically able to cope with the surgery and it isn’t too risky for you. You will be reviewed by an anaesthetist and may require additional tests, to check your general health and fitness. If you’ve been having problems with eating and have lost weight, you may be given extra help and support with your diet to help prepare you for the surgery. If you smoke, stopping smoking or cutting down before your surgery will help reduce the risk of complications after your surgery.

Going into hospital for pelvic exenteration

Before your surgery, one of the medical team will come to see you and explain the surgery to you, so you have an idea of what to expect in the days following the surgery. You’ll also see a nurse who specialises in the care of people with stomas (called a stoma nurse). They will explain about stomas and answer any questions you have about them. After the surgery, the stoma nurse will teach you how to look after your stomas and give you information and support to help you cope with any problems.

What happens during the surgery?

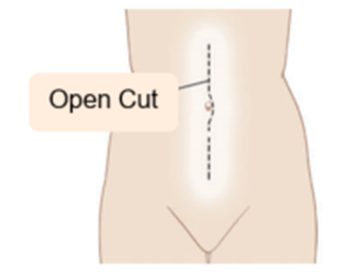

You will be given a general anaesthetic, which means that you will be asleep for the entire procedure. Usually, an epidural anaesthetic is used as well so that we can offer you pain relief following the procedure to make you more comfortable. The surgery is carried out through a vertical incision (see below)

The inside of your abdomen is examined to make sure that the cancer has not spread. Sometimes biopsies (small pieces of tissue and lymph glands) are taken and sent immediately to the pathologist, who examines them, also to make sure there has been no cancer spread.

If the cancer has spread beyond what can be removed, the surgery is stopped and the incision is closed without doing any more surgery. If the biopsies are negative and there is no spread, the surgery continues.

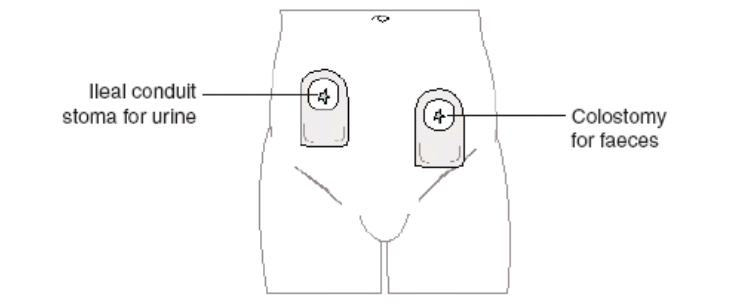

Pelvic exenteration is a long surgery. It usually lasts about eight hours and there will be at least two surgeons. They will try to remove the cancer and reconstruct or replace some of your organs. After the pelvic exenteration surgery, you may have a urostomy and/or colostomy.

A urostomy is a new way for your urine to leave your body after your bladder is taken out. An ileal conduit is the most common type of urostomy. The surgeon removes a section of the small bowel and joins the tubes coming from each of the kidneys (ureters) to one end of it. They bring the other open end of the bowel out through a small opening (stoma) in the skin of the abdomen wall. Urine made by the kidneys will pass out of the body through this stoma. After the surgery, you’ll wear a flat, watertight bag over the stoma to collect your urine. The bag will fill with urine, and you’ll need to empty it regularly.

A colostomy is a new way for your bowel motions to leave your body after your bowel and anus are removed. After the lower part of the bowel (rectum) and anus is removed, the remaining end of the bowel will be brought up to an opening (stoma) on the abdomen. This is known as a colostomy. You’ll wear a bag over the stoma to collect bowel motions.

The stoma nurses will see you after the surgery and during your inpatient stay and will offer education on how to look after stoma(s). They will organise stoma supplies (bags) for you and for a stoma nurse to support you in the community. Alternatively, they may arrange for you to visit them in hospital after you have been discharged.

What happens after surgery?

After a pelvic exenteration surgery, you’ll be in an intensive care or high-dependency unit for the first few days, and will probably be in hospital for about 2–3 weeks. When you wake up after the surgery, you will have dressings on your abdomen. You may also have:

- A drip going into a vein in your arm or neck (intravenous infusion). This will give you food and fluids until you are able to eat and drink again. It may also be used to give you pain relief.

- A fine tube going into your back (epidural). This may be used to give you drugs that numb the nerves and stop you feeling sore.

- A tube that passes down your nose, into your stomach or small intestine. This is called a nasogastric tube and it allows any fluids in the stomach to be removed so you don’t feel sick. You may need this for a few days.

- One or more drainage tubes coming from your wound to collect any extra fluid or blood. These will be removed when the amount of fluid draining has reduced.

- A bag covering your colostomy and/or urostomy.

You may feel much more tired than usual after your surgery as your body is using a lot of energy to heal itself so you may need to take a nap for the first few days.

An exenteration can also be emotionally stressful and many women feel tearful and emotional at first – when you are tired these feelings can seem worse. For many women this is often the last symptom to improve.

It usually takes a few days before your bowels, and colostomy if you have one, start to work normally and you may experience discomfort associated with a build-up of wind. This usually resolves itself, but if it becomes a problem the nursing staff may provide some peppermint water to drink and encourage taking gentle exercise. You may want to bring a bottle of baby’s gripe water into hospital with you as many women feel that this is effective in relieving wind pain.

It is important to keep your genital area and any abdominal wounds clean. A daily shower is advisable paying particular attention to these areas. Avoid the use of highly scented soaps, bubble bath and vaginal deodorants, etc. You may have dissolving stitches in your wound, in which case you will be advised by the nursing staff how to care for them. If you have clips, staples, or stitches (sutures) which need to be removed, the nursing staff will explain how to care for your wound and advise you when they will be removed.

Recovering after a pelvic exenteration

It can take a while to recover after pelvic exenteration. After the surgery, your nurse will encourage you to move about. They will guide you on leg movements and breathing exercises, and will help you get out of bed. You’ll be able to do more for yourself a few days after the surgery.

You’ll need support when you get home after surgery. The hospital staff can arrange help for you if you live on your own. Nurses will visit you at home to help look after your wound and stomas. A stoma nurse will help you change your stoma bags. It can take a while to get used to living with a stoma, as it can be difficult to start with.

Try to take things slowly after your surgery. Over time, you will be able to do more and you will have more energy. It may take up to 12 weeks after surgery before you start to feel better. It may take up to six months after surgery for your body to heal. Only do as much as you feel able to.

Risks and complications of surgery

There are risks and complications associated with any major abdominal surgery. It is important to realise that these risks and complications are uncommon. Your surgeon will discuss with you in more detail your individual risks.

The surgery is carried out under general anaesthetic. All surgeries carry a risk from anaesthetics but this is minimised due to modern techniques. You will meet the Anaesthetist prior to your surgery who will explain in more detail the type of anaesthetic you will receive and any individual specific risks.

Visceral injuries

This means injury to the ureters or to the remaining pelvic structures or organs. These complications would usually be found during the surgery and dealt with immediately. In rare cases the problem may not become apparent for a few days after the surgery and this may require a second surgery to resolve the problem.

This may include developing a leak from the bowel at the point at which it has been re-joined (anastomoses). The medical team on the ward will observe closely for any signs of this occurring and you will be provided with information on what to watch out for once discharged home.

Blood loss/Clots

You will have some blood loss at the time of your surgery and a blood transfusion is sometimes required in about one in five surgeries. Rarely, there may be internal bleeding after the surgery, making a second surgery necessary.

Occasionally it is possible to develop blood clots in the veins of the leg or the pelvis, rarely this can lead to a blood clot in the lungs. Moving around as soon as possible after your surgery can help prevent this. The physiotherapist will visit you after your surgery to give advice and to help with your mobility. We will give you special surgical stockings (known as ‘TEDS’) to wear whilst you are in hospital.

To reduce the risk of blood clots following your surgery you will be given injections to thin your blood during your stay in hospital and for approximately 28 days on discharge. This is an anti-clotting medicine that reduces your body’s tendency to form blood clots and protects against thrombosis. It is unlikely that you will experience any problems with these injections. The most common problem is bruising or discomfort around the injection site. However, you should bring any of the following symptoms to the attention of your doctor or nurse: unexpected bruising or bleeding, red urine or black stools, or a rash at the injection site. Patients with a previous DVT are at greater risk for additional clots and should make their surgeon aware of this condition.

Infection

There is also a small risk of developing an infection which may be in the chest, wound, pelvis or urine. To reduce this risk you may be given antibiotics just before the start of the surgery. After an anaesthetic and a surgery there is a risk that you may develop a chest infection. Chest infections are caused by bacteria or a virus. General anaesthetics affect the normal way that phlegm is moved out of the lungs. Pain from the surgery can mean that taking a deep breath or coughing is difficult. As a result of these two things, phlegm can build up in the lungs. Within the phlegm an infection can develop. You will be seen by the physiotherapist after your surgery who will provide guidance and explain the importance of breathing exercises.

Superficial wound infections normally occur within the first week after surgery. You may experience pain around the surgical site, redness and/or a slight discharge, usually caused by skin staphylococci. You will be reviewed daily by the ward team and prescribed additional antibiotics should they be required. You can assist by keeping the wound clean and dry, assisted by the nursing staff. Wound breakdown (full dehiscence) can rarely occur in five in 1000 women needing return to theatre and re-suturing of the wound. You may experience some superficial skin separation once the clips have been removed from your midline incision, this can be managed routinely by the nursing staff on the ward and if needed by district nurses in the community upon discharge. We do not re-suture these wounds but allow them to heal by secondary intention (this involves leaving the wound open and allowing it to heal on its own over time).

Some patients take longer to heal than others, particularly people with more than one illness.

A patient with a chronic illness, an immune system problem, or sickness in the weeks prior to surgery may have a lengthier hospital stay and a more difficult recovery period. People with Diabetes typically have a longer healing time, especially if blood sugar levels are poorly controlled.

Loss of Skin Sensation

Many patients experience numbness and tingling around their surgical site, for some it is a temporary condition; others find it to be a permanent complication. Creating an incision requires the surgeon to cut through nerves, which send messages between the body and the brain. If enough nerves are cut, the area surrounding the surgical site may have numbness or a tingling sensation. Depending on the location of the damage, the nerve may regenerate, allowing sensation to return to the area over the course of weeks or months. In other cases, damage to the nerves may be too great for the body to repair, resulting in permanent numbness or tingling.

With any gynaecological surgery there is some risk of death but as exenteration is a very complicated and long procedure, sometimes taking over eight hours to perform, the risks are considerably greater than usual. If you do have any concerns about the risk of complications, please discuss them with the consultant or a member of his/her team (doctors or nursing staff) and your questions will be answered as clearly and as honestly as possible.

Common questions

Below are some general questions and answers about having an exenteration. If you need any more details or have other questions or concerns, your nurse or doctor will be happy to help.

Will my life be different with a stoma to pass urine through (ileal conduit) and/or a stoma to pass bowel motion through?

Your life will be different and it will take some adjusting to. Your gynaecological-oncology team will be here to support you and your nurse specialist (key worker) is available to talk to you. The stoma nurses will be here to support your learning of how to physically look after your stoma(s) and how to deal with them psychologically. You may have some difficulty coming to terms with how your body looks with the stomas. You may choose to discuss these with the ward team, stoma nurses, and/or your gynaecological-oncology surgeons.

Do I still need to have smear tests?

If you have had pelvic radiotherapy already you will not have been having cervical smears. After an exenteration where the uterus (womb) and cervix (neck of the womb) and possibly the vagina (either partial or total) have been removed, it will not be necessary to have smear tests.

How will I feel emotionally?

You may experience many different emotions, including anger, resentment, guilt, anxiety and fear. These are all normal reactions and are part of the process people go through in trying to come to terms with major surgery and with the uncertainty cancer brings. It’s important to remember that many people who have pelvic exenteration are cured of cancer and go on to live full and satisfying lives.

Talking about your emotions isn’t always easy, but it can help reduce feelings of stress, anxiety and isolation. Try to let your family and friends know how you’re feeling so they can support you. Many people get support through the internet. There are online support groups, social networking sites, forums, chat rooms and blogs for people affected by cancer. You can use these to ask questions and share your experience.

Sometimes it’s easier to talk to someone who is not directly involved with your illness. You could ask your hospital consultant or GP to refer you to a doctor or counsellor. Some counsellors are specialists in the emotional problems of people with cancer and their relatives.

Will I be able to have sex?

The physical changes to your body after the surgery will mean changes to your sex life. You’ll need to make both physical and emotional adjustments. The surgery varies from person to person, and the effects it has on sexuality will also vary. Your surgeon and specialist nurse will talk you through the changes you may experience.

Adjusting to changes in how your body looks and responds takes time. Many people need to talk through their feelings and emotions. Some feel nervous about how their partner will react to their body. There is no right or wrong time, or way, to talk about these issues. You can wait until you and your partner feel ready.