What is ICSI?

ICSI is a fertility treatment has been a treatment option since 1992 to treat couples where the cause of infertility is a severe sperm problem. Before the development of ICSI the only treatment option would be to use donor sperm. ICSI offers the hope that men with sperm problems can have children conceived using their own sperm.

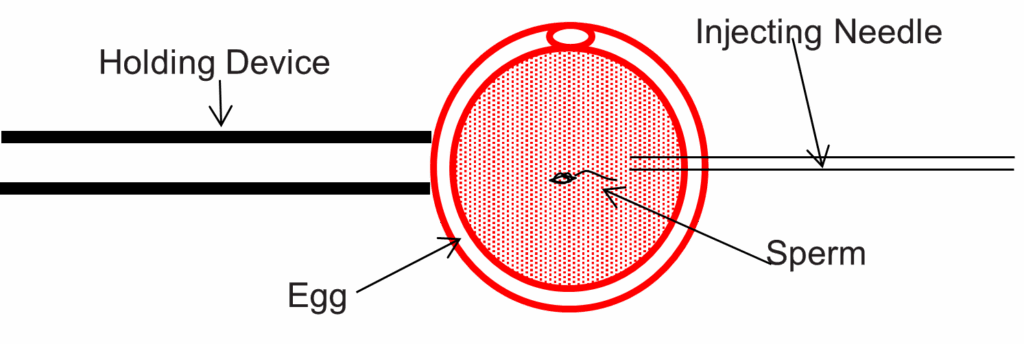

Conventional fertility treatments rely on the sperm to fertilise the egg without assistance. However, if the number or motility of the sperm (movement in a forward direction) were much reduced there is a high chance that fertilisation of the egg would not happen. ICSI involves picking up a single sperm with a very fine needle and injecting it directly into the egg (see below).

ICSI is actually a modification of conventional IVF. For the couple undergoing ICSI the drugs and procedures are identical to conventional IVF treatments. The difference is how we handle the sperm and the egg in the laboratory.

When is ICSI required?

ICSI is used when sperm investigations have revealed a severe problem that may prevent the sperm from fertilising the egg naturally or by conventional IVF.

This may occur in the following circumstances:

- When the sperm count is low

- When the sperm are not moving normally.

- When there are very low numbers of sperm with a normal shape.

- When sperm has been retrieved directly from the epididymis (PESA) or the testicles (TESE) or from the urine or by electro ejaculation.

- If there is a high level of antibodies in the semen impairing sperm function.

- When there has a been previous cycle with low or failed fertilization

ICSI offers hope to men with very few sperm (oligospermia) or no sperm in their ejaculate (azoospermia), or sperm with low motility (asthenozoospermia), who previously would not have been able to father their own genetic offspring.

How successful is the ICSI Procedure?

It is unlikely that all the eggs collected will be suitable for ICSI, as only mature eggs can be injected. Typically, about 70 – 80% of eggs collected are mature. On average about 65% of injected eggs will fertilise.

ICSI is an invasive procedure, and it is inevitable that some eggs will be damaged by the procedure or will not fertilise. However, all ICSI practitioners are experienced embryologists who undergo an annual competency assessment ensuring that over 90% of all eggs injected are undamaged.

The Human Fertilisation & Embryology Authority (HFEA) keep a record of all IVF and ICSI procedures carried out in the UK. Our most recent results as well as the national figures are shown on the separate RESULTS SHEET.

Factors Affecting the Success Rate of ICSI

Female Factors – In order to withstand the injection process, eggs need to be fairly robust and of good quality. It is known that the egg quality is reduced in older women and in women who smoke. The success rates of ICSI and conventional IVF is lower in older women (older than 38) and women who smoke.

Male Factors – If there are no moving sperm present in the sperm sample, it is difficult to identify live sperm. Under these circumstances it may be necessary to select a non-moving sperm for injection. A large number of these sperm will be dead and therefore fertilisation rates will be poor under these circumstances. There is also some evidence that injecting sperm with abnormal head shapes may be associated with poor results.

Possible Hazards of ICSI

ICSI has all the medical hazards associated with conventional-IVF, however with ICSI there are also additional concerns. In natural conception and conventional-IVF a sperm has to swim to meet the egg, be able to bind with surface of the egg and penetrate the outer layer of the egg before it can fertilize the egg. Normally only healthy sperm are capable of doing this. However, with ICSI a sperm is selected based on its appearance and motility and injected into the egg thus bypassing the natural selection processes. There are concerns that an abnormal sperm could be selected for injection, and this could increase the potential risks to children born as a result of ICSI.

Over 5 million children have been born globally following ICSI and several follow up studies have been published in order to assess the safety of ICSI. The main genetic and developmental concerns regarding ICSI are detailed below.

Possible inheritance of genetic and chromosomal abnormalities

Inheritance of the cystic fibrosis gene mutations. Some men who have no sperm in their semen samples are born without the tubes that carry the sperm from the testis to the penis. Two thirds of these men are also carriers of certain cystic fibrosis genes. Men with this problem and their partners may therefore wish to undergo genetic testing before proceeding with ICSI. We will discuss this with you fully before your treatment starts.

Sex chromosome defects and the inheritance of sub fertility. A small proportion of men with sperm problems have part of the Y chromosome missing (deleted). Certain genes on the Y chromosome are involved in the production of sperm, and if parts of these genes are missing this may account for the low numbers of sperm in the semen. If the sperm with these deletions are selected to create the embryo this may result in the same type of sperm problem being passed from father to son.

Abnormal numbers or structures of chromosomes, particularly the sex chromosomes (X and Y), may be associated with infertility in both men and women, and babies born from ICSI treatment have a slightly increased risk of inheriting these abnormalities. Studies have found that up to 3.3% of fathers of ICSI babies have abnormal chromosomes. It is estimated that up to 2.4% of the general population have a chromosomal abnormality. If we think there is a high chance of a sex chromosome problem, we may advise a blood test to check your chromosomes.

Novel chromosomal abnormalities

Sperm and egg production is a complicated progress. Even in individuals with a normal number of chromosomes, sperm or eggs may be produced that potentially have an abnormal number. Unfortunately, it is not possible to detect beforehand which eggs or sperm have chromosomal abnormalities. Normally these sperm or eggs might not be able to participate in natural fertilisation but may be selected to be used in ICSI. Babies born after ICSI have been reported to have new chromosomal abnormalities in up to 3% of cases. This is higher than the rate found in the general population of around 0.6%.

Possible Developmental and Birth Defects

Birth Defects

The studies to date provide reassuring information. The incidence of major birth defects e.g., cleft palate, is between 1 and 5% this seems to be the same in both the general population and in babies born following ICSI. Minor birth abnormalities are relatively common with an incidence of up to 15% in the general population and up to 20% of ICSI babies.

Developmental Delays

Concerns regarding possible delays in child development were raised following a recent study involving a relatively small number of children born after ICSI who showed signs of developmental delay at 1 year of age. However, problems that have been linked with ICSI may have been caused by the underlying infertility, rather than the technique itself. Other studies have not shown this link and further research is needed in this area.

Possible Risks During Pregnancy

Miscarriage

It is thought that one of the commonest causes of miscarriage is a genetic problem in the developing foetus. Normally sperm and eggs that contain genetic problems would not be able to produce a healthy embryo. It is possible that during ICSI a sperm or egg would be selected that contains a genetic problem leading to formation of an abnormal embryo. Usually, these embryos would not implant in the womb, however if they did this may lead to higher risk of miscarriage

Please read our unit booklet for information on the following;

- The HFEA

- Welfare of the Child

- Pregnancy and Success

- General advice prior to conception

- Ethics Committee

- Counselling

- Complaints and Contacts